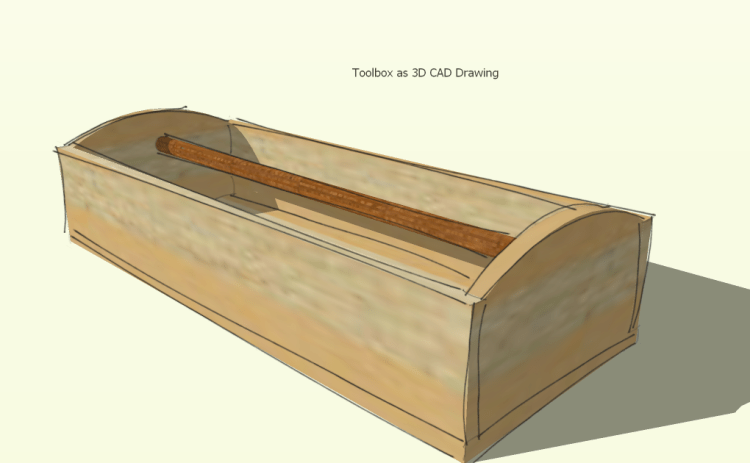

Took over our conference room to work through some design challenges today. My students used Google SketchUp to start creating jewelry boxes, art car vehicles and bookshelves.

During the Art Car class, I led the group building a 3D model on the big (like 50-60″ screen) TV. Computers+big screen TV+3d modeling software+we are building a car = interested, motivated students. Or so I thought. I turn around, two students are asleep.

I have only three kids on the dang project. Terrible numbers. Mendoza line terrible.

I quickly got out the sketchbooks and pencils. More success, more interaction.

So, what I remembered and learned again the hard way today – the project material supply (in this case, laptops w/ the programs added to it) has to match the student’s learning styles (one-on-one direct involvement is the only way) and interest. Sometimes, this is hard to make happen. Like in a science lab.

A science lab means 4 (5 kids/project?) to 15 (dyads) to 25 (each kid gets an experiment) per class. If an average middle school science teacher has 100 or so students, and there is two to three science teachers per grade, we are talking about an enormous amount of dead frogs for a biology lab. I like to run a “bridge to nowhere” contest where students build bridges from packs of 50, 100 and 150 craft sticks. If I did that in a large student population (100 students paired up), I would end up with 5 boxes of 1000count sticks, enough hot-glue to cover that (who knows that amount…) and the tool cost of 10-15 glue guns. It’s an investment closer to $50 to $100 a learning cycle. And that’s a cheap lab. You really don’t want to know the cost of a dead frog. So instead of engaging a students ability to learn with their hands or observation of real world phenomena, only students who learn best by textbook will be served. Or rather – only those students who learn by lecture, reading text and maybe watching movies will be best served. Tactile, kinesthetic learners like my students are out of luck.

One of my students will build a bookshelf from pine this semester: $40 of pine. 1 student. If I had more kids, could my school keep an educational woodshop/environmental science/art class operating (three teacher’s salary + benefits, supplies, tools, space/housing costs and insurance)? We have a budget for my program, and it’s HUGE to me. I’m very, very, very grateful for it. Because I remember the budget for my last job: $80 a semester. If my schoolteachers had an operating budget like that, it’s little wonder why my inner-city, low-income students never had a single science lab. How could they? 80 bucks and 100 students won’t even get each student a candy bar. I think for all the uproar over how science education and creative arts have left the modern education system, we should also remember one reason why we lost them first: they are expensive.

Computer labs seem to have taken over as creative arts labs. Computers represent a smaller 5-yr investment than a woodshop. Many educational leaders get blinded by the screen and think computers can replace true tactile learning. Computers don’t replace it. The two asleep students refused to even try the CAD program – it’s why they did pen-and-paper sketch work.

So, to sum up. Support your creative, tactile arts teachers if you still got’m. Get’m some paint. Throw a 2×4 my way. I won’t say no.

And remember to bring enough computers to keep everyone involved in your third period class. And some paper and pens.

It’s time to start drilling holes for stakes.

It’s time to start drilling holes for stakes. I raised the stakes off the ground with rebar, then drill 1/2 in. holes through the timbers. I’m relying on friction between the rebar and wood to keep the pieces together and minimize movement. I’ll tell you how that brilliant decision turns out when the stakes get driven in.

I raised the stakes off the ground with rebar, then drill 1/2 in. holes through the timbers. I’m relying on friction between the rebar and wood to keep the pieces together and minimize movement. I’ll tell you how that brilliant decision turns out when the stakes get driven in. When this particular projects done, I’ll see what I can do to assemble some before and after shots.

When this particular projects done, I’ll see what I can do to assemble some before and after shots. The Production Co is working on building some awesomeness prototypes (I’m thinking lamp stands, stained a deep cherry red?). We’ve failed completely at actually finishing some products for tomorrow’s Valentines/Rodeo sale, but hey, we tried. Bad weather & the normal prototype issues got to us.

The Production Co is working on building some awesomeness prototypes (I’m thinking lamp stands, stained a deep cherry red?). We’ve failed completely at actually finishing some products for tomorrow’s Valentines/Rodeo sale, but hey, we tried. Bad weather & the normal prototype issues got to us.